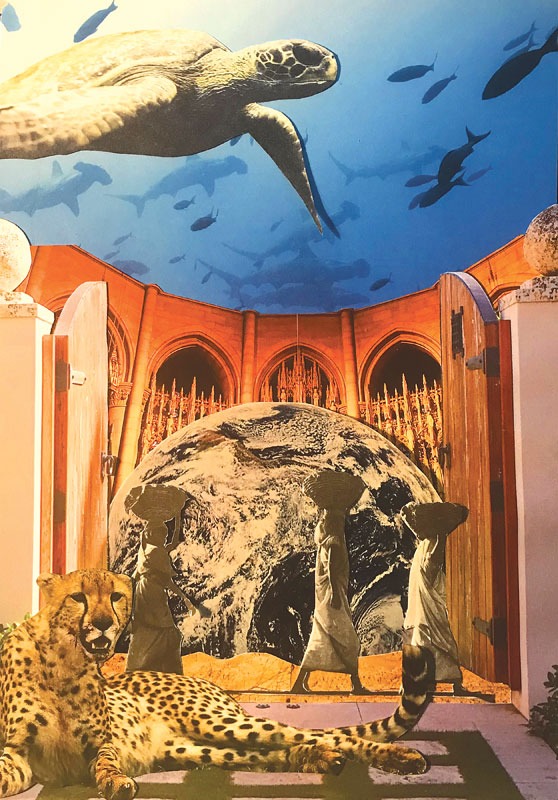

Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

Editors’ Note: This article comes from the Summer 2021 edition of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “The World We Want: In Search of New Economic Paradigms.”

When, back in November 2018, Sunrise Movement organizers sat in protest in House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office and called for a Green New Deal, they broke a cycle of stale federal climate advocacy. The Green New Deal caught people’s imagination, because it opened a new frame that took us beyond “jobs versus climate” or reliance on market solutions like pricing carbon and toward the idea that tackling climate could build a whole new way of organizing our economy and our society. It could fight parts per million and police brutality at the same time. It could build renewable energy while bolstering the Fight for $15. The Green New Deal, in essence, could help pull us out of the depths of the late-capitalist, neoliberal era of the past few years and into a resilient solidarity economy.1 Therein lay potential to motivate and mobilize fierce coalitions for change.

Eighteen months later, the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world and shifted the playing field yet again by revealing the fragility of our current systems. The U.S. privatized healthcare infrastructure collapsed in the face of the emergency.2 Millions of people lost their family members, their jobs, and their homes in the midst of a haphazard economic shutdown because of the cruelty of a system engineered to serve an elite class. The exacerbated and racist inequities of economic and health systems paired with extreme police brutality came to a head after the Memorial Day police murder of George Floyd, when communities rose up in defense of Black lives.3 The devastation communities experienced in 2020 proved—if further proof were needed—that the United States is in critical need of systemic transformation.

The COVID-19 pandemic also drew the curtains back on some key arguments surrounding the Green New Deal. For instance, almost overnight, concepts of federal spending changed. Before, the Green New Deal had been attacked for the scale and scope of investment that it proposed. But in 2020, the Federal Reserve injected trillions of dollars into the U.S. economy, including direct deposits of cash into people’s bank accounts, so that people could survive. So far, fears of out-of-control inflation have proven unfounded, and austerity has become “unfashionable.”4 What’s more, the past year also showed that we can still realize another critical tenet of a Green New Deal: the ability to mobilize quickly toward a common goal. Scientists moved faster than ever before to create the COVID-19 vaccine in under a year. Before that, the mumps vaccine was the fastest, at four years of development.5

But within this upheaval of U.S. conceptions of spending, scaling, and mobilization that greatly bolstered the case for the Green New Deal, there also lies danger in what the Green New Deal could become. The U.S. government handed over the management of critical programs like the Main Street Lending Program to companies like BlackRock; in turn, many small businesses—particularly those owned by people of color—didn’t see a cent, while fossil fuel companies grabbed outsized slices of the pie.6

Similarly, while the vaccine development sprinted beyond its predecessors, companies are holding steadfast to the patents and thus stopping mass production of the cure for millions. Pressure is growing, but those patent rights haven’t been waived yet, even if the Biden administration in May did shift to a position favorable to waiving some intellectual property protections around the vaccines. This shows the true viciousness of public–private partnerships, with public money funneling into pharmaceutical companies, creating corporate gain and apartheid between the Global North and South: the vaccinated and the dying.7 With the climate crisis a clear global phenomenon, will technologies and global cooperation fall into the same traps?

The COVID-19 pandemic not only opened up doors for organizing for a just Green New Deal but also gave us warnings. It made the question of who benefits all the more pertinent. For instance, a Green New Deal could enrich a union-busting Elon Musk as, pumped up by public subsidies and incentives, he makes electric cars for the middle and upper class. In doing so, it will have failed at the possibility of transforming the economy into something more humane through climate mobilization.

Climate action holds the possibility of actively dismantling capitalism, white supremacy, and imperialism—in short, building a solidarity economy. But to do so will take intentional investments in alternative models of ownership that return the economy and the means of production to the people, untangling racist policies and practices of the past to build new social fabrics that empower rather than exploit, and engaging in local to international partnership with a frame of a collective future.

The interplay between the movements for the Green New Deal and the solidarity economy is crucial for this sort of shared success. The growing local manifestations of the solidarity economy affirm the models and stand out as exemplars of what the Green New Deal could achieve. Particularly during the COVID-19 crisis, the solidarity economy plugged the cracks when, under the Trump administration, the federal government failed. Mutual aid funds held together families on the brink.8 Employees, when confronted with office closures or major changes in their workplace, responded by engaging in union organizing drives and pushing for worker ownership, recognizing the power they hold in the workplace as they did so.9 Local support networks for food and medical help bolstered the uprisings for racial justice. With this experience, communities brought their experiences to federal fights, calling for rent cancellation or for providing direct cash support to families.10 The growing solidarity movement here has thus acted as a laboratory for more national calls to action, moving the needle toward more transformative politics.

Paramount here is a marriage of scale between large, federal public institutions, policies, and programs and grassroots, place-based projects. For instance, the Green New Deal allows for massive funding that explicitly achieves dual goals of decarbonization and democratizing the economy. In return, the local groups who receive this funding, as members of those communities themselves, can be important connectors to communities who need it most. Furthermore, they can strengthen systems of participation and democratic practice that can, in turn, help keep the federal level accountable and increase democratic participation across the board.

Let’s reflect on some examples.

The fight for public control over utilities that has gained steam over the past few years pulls at this tension of scale in interesting ways. In some cases, strategies for community ownership over solar grids or rooftop solar can be put in tension with fights for larger-scale pushes for a state-level takeover of a utility. However, this need not be the case. One of the compelling opportunities in the fight for public power is the ability to take over large swaths of the energy system at once, while also reorganizing the system to bake in concepts of community as loci of decision making. My organization, The Democracy Collaborative, recently launched a report about how expanding and reforming the New York Power Authority (NYPA) could support New York’s climate goals.11 NYPA is an already-operating public power energy generator in New York, created in the early 1930s by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, when he was governor, to counter corporate power; it foreshadowed parts of the New Deal.12

The report brings that New Deal institution into the era of the Green New Deal. For instance, it proposes that NYPA take direct public ownership stakes in large-scale renewable energy projects, reorganizing the status quo around these sorts of projects so that they are in partnership with local communities (instead of steamrolling their demands). It proposes regional hubs that operate as democratized spaces for: dialogue with those most impacted by issues of siting; community benefits; jobs; and integrated planning with the larger community, so that development is directly informed. NYPA could also invest in, streamline, and directly fund community-led programs for distributed renewable energy, to build up climate resiliency in the state. Working in relationship with Black-led and climate/environmental justice groups that have deep ties to the community is critical to ensuring that investments flow to those who need it most and can actively engage the community.

Similarly, the fight to nationalize the fossil fuel industry can be seen as an opportunity to use the power of the federal government to take over a hurtful industry while ceding back control to communities. In a recent paper we published as fossil fuel companies’ share prices dropped precipitously during 2020, we outline potential opportunities for federal intervention to support ending extraction.13 The report advocates creating a Just Transition Agency to act as a holding company for the acquired fossil fuel companies with the express goal of a phase-out grounded in just transition principles. With federal support, regions and communities could receive funds and expertise to wind down the extractive industries and replace them with a more resilient, more diverse economy. Such a program could even cede land and territory back to Indigenous communities from whom it had been stolen, and thus revitalize the area and the communities.

Another example of how massive shifts in public procurement could be a mechanism for major economic transformation: If the federal government were to mobilize a substantive cohort of the Civilian Conservation Corps to invest in our natural systems (simultaneously creating new economy-wide wage floors) or seek to retrofit every single public building, they would need supplies and manufacturing. By setting clear standards for their procurement that prioritize contracts with worker-owned firms, unionized workplace environments, and places that actively support entry programs for BIPOC workers into sustaining, good jobs, the federal government could create whole new forms of worker control over the means of production. The space could open up even more if coordinated with massive funding for worker-ownership technical support programs or even an employee ownership fund focused on the carbon-free economy. For instance, New York City has developed an audacious Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative to support worker cooperatives as places to build worker autonomy and particularly to support women- or BIPOC-owned worker cooperatives.14

New technologies can contribute to addressing our climate emergency, of course, but fundamentally our global climate crisis is not a problem of technology but rather a social problem. A Green New Deal that doesn’t cut to the heart of racialized capitalism is certain to be inadequate. Perhaps some technological innovation will keep sea-level rise at bay, but no technological legerdemain will save Black families from crumbling infrastructure or release society as a whole from global resource constraints. A Green New Deal, however, by massively reordering how governments and our largest economic actors function, and by fostering a public culture of mutual caring and support, can be the key to unleashing the full potential of solidarity economies, where power and wealth are rooted in communities.

Notes

- Kate Aronoff et al., A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal (New York: Verso Books, 2019).

- Leslie Cook and Hannah Kuchler, “How coronavirus broke America’s healthcare system,” Financial Times, April 30, 2020.

- Sean Illing, “The ‘abolish the police’ movement, explained by 7 scholars and activists,” Vox, June 12, 2021.

- Douglas Webber, “Capitalism and the coronavirus crisis: the coming transformation(s),” The Conversation, October 28, 2020.

- Philip Ball, “The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines—and what it means for other diseases,” Nature, December 18, 2020.

- “30 Groups Release Letter to Fed Raising Concerns Over Details of BlackRock Deal,” BlackRocksBigProblem, press release, March 27, 2020; and Dan L. Wagner et al., “Bailed Out and Propped Up: U.S. Fossil Fuel Pandemic Bailouts Climb Past $15 billion,” Public Citizen, November 23, 2020.

- Alexander Zaitchik, “How Bill Gates Impeded Global Access to Covid Vaccines,” New Republic, April 12, 2021.

- Dorothy Hastings, “‘Abandoned by everyone else,’ neighbors are banding together during the pandemic,” PBS, April 5, 2021.

- Celine McNicholas et al., “Why unions are good for workers—especially in a crisis like COVID-19,” Economic and Policy Institute, August 25, 2020.

- Celine Castronuovo, “Omar reintroduces bill seeking to cancel rent, mortgage payments during pandemic,” The Hill, March 11, 2021.

- Johanna Bozuwa et al., A New Era of Public Power: A vision for New York Power Authority in pursuit of climate justice (Philadelphia: The Democracy Collaborative and climate + community project, May 12, 2021).

- Rock Brynner, Natural Power: The New York Power Authority’s Origins and Path to Clean Energy (New York: Cosimo, 2016).

- Johanna Bozuwa and Collin Rees, The Case for Public Ownership of the Fossil Fuel Industry (Washington, D.C.: The Next System Project, The Democracy Collaborative, and Oil Change International, April 2020).

- NYC Small Business Services and Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, Working Together: A Report on the Sixth Year of the Worker Cooperative Business Development Initiative (WCBDI), 2021). And see Steve Dubb, “Building a Worker Co-op Ecosystem: Lessons from the Big Apple,” Nonprofit Quarterly, February 5, 2020.

0 Commentaires