Click here to download this article as it appears in the magazine, with accompanying artwork.

This article is from the Winter 2021 issue of the Nonprofit Quarterly, “We Thrive: Health for Justice, Justice for Health.”

In order for me to thrive as a person I need to be doing something that I love and be surrounded by people that I love and have a community that I can call my own.—Lara1

Thriving means having your identity supported, your identity affirmed . . . being in a situation where you can learn, fail, make mistakes, and still understand yourself as someone who will be capable of greatness and is worth greatness.—Dante2

Humans have imagined thriving across our entire history, from Iwa (living virtuously) to eudaemonia (good spirit) to contemporary theories of flourishing.3 Models abound. They often reflect the voices of those empowered to articulate and record such ideas (scholars, philosophers, politicians), who, in turn, reflect the power structures of the societies in which they reside.

There is no single accepted model of thriving. Some people approach it with a physiological focus, or a psychological one. Sometimes, people use resilience and thriving interchangeably; some call it flourishing.4 My research focuses on intersections of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, age, and ability. And in doing so, I have been able to advance an inclusive, intersectional, and developmentally grounded model. However, within the minuscule pool of scholarship that centers Black LGBTQ+/SGL youth and young adults, for example, there is almost none attending to their lives beyond surviving oppression. Select another intersectional suite of identities and you’ll find the same. Disabled trans women? Native girls? Nonbinary Latiné adults? If anything has been written, it is most likely hardship centered. This is understandable (we want to end suffering), but insufficient.

Rejecting the Deficit Approach, the Medical Model, the Status Quo

We need to suspend “‘damage-centered’ research . . . that intends to document peoples’ pain and brokenness to hold those in power accountable for their oppression” but “simultaneously reinforces and reinscribes a one- dimensional notion of . . . people as depleted, ruined, and hopeless.”5 Under our dominant medical model, people under duress whose coping or survival behavior is pathologized must be “fixed” so they can fit in. Psychologist Martin Seligman calls for the “[curtailment of this] promiscuous victimology,” elaborating that “in the disease model the underlying picture of the human being is pathology and passivity The gospel of victimology is both misleading and, paradoxically, victimizing.”6 Focusing too narrowly on problems and what writer and professor Edward Brockenbrough calls “victimization narratives” gets in the way of building something visionary and liberatory, something that needs to be, and is already being, shaped by marginalized people themselves.7

I feel whole when I really….. nurture my sense of spirit, which is in my creative outlets, which is in nature, which is in cultivating just the little things, cultivating gratitude and positivity.—Sailor8

We’re putting most of our energy into making people “fit” into systems and institutions that are fundamentally flawed—violent, even—and, in the process, reinforcing the belief that these sociopolitical structures are natural. They are not. It’s not a flex to participate for the sake of participating in a society that’s designed to destroy us. Assimilation, compliance, compromising personal needs, and becoming smaller than we authentically are all require rejection of one’s true self. We activate our precious energy for survival instead of passion, pleasure, fulfillment, and innovation. We also find ourselves increasingly disconnected from one another. Laurence J. Kirmayer and colleagues note that “Aboriginal values and perspectives emphasizing interconnectedness, integration, and wholeness can provide an important counterbalance to the ways of thinking about resilience . . . that tend to dominate current scientific writing.”9, By considering “the whole state of the person,” as well as the communities and systems within which they exist, an “Aboriginal perspective [moves] resilience away from a simple, linear view of risk exposure, resilience, and outcome, toward a more complex, interactional and holistic view [that] . . . includes the role of traditional activities, such as spirituality, healing practices, and language in dealing with change, loss and trauma.”10

Beyond resilience, we need to create the space and the conditions to design a much better now and a much better future. Here, I highlight what Black LGBTQ+/SGL communities have taught us about the dimensions of thriving, offering a way to move forward. Hardship is not the only story.

So, when I go out with a bunch of queer folks of color and we’re all together in that space, but also then . . . being able to see all these other queer folks of color who I don’t know, but I feel this connection with, and see them joyfully losing their inhibitions and finding joy, in ways that I see queer folks of color not really being able to completely find joy in their daily interactions . . . there’s a beauty and a joy that I find there.—Dante11

Black LGBTQ+/SGL people have crafted moments, spaces, and practices of activism, belonging, wellness, beauty, and possibility, even as they have revealed and pushed back against heavy challenges. L. H. Stallings talks about the “imaginative, agentive, creative, performative, uplifting transitional space[s] established and occupied by queer youth of color”12—while Bettina Love celebrates identity formation and expression grounded in “performance of the failure to be respectable” and the freedom granted by “contradictory, fluid, precarious, agentive, and oftentimes intentionally inappropriate” ratchetness.13 The act of claiming joy or pleasure, especially when in defiance of norms of respectability, is healing work. The tendency to focus on adversity and pathology leaves little space for a concept like pleasure. It then fails to recognize the immense power that Black LGBTQ+/ SGL people have called upon for generations in the face of oppression. More than simply being self-accepting, insisting upon self-expressing (often ratchetly) is a crucial, adaptive facet of thriving—really, for any oppressed community. It is holistic stress relief.

Consider James Baldwin’s 1956 novel Giovanni’s Room, which he was initially told to burn due to its “homosexual” content.14 Consider Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), founded by Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera in 1970.15 Consider the Ballroom culture so lovingly portrayed in the films Vogue Knights: A Short Documentary on Ballroom Culture in Hell’s Kitchen (2014) and Kiki (2016), as well as the scholarship of Marlon M. Bailey16 and activist scholarship of Michael Roberson (and his Ballroom Freedom School).17 Consider the work of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, like her chapter “Something Else to Be: Generations of Black Queer Brilliance and the Mobile Homecoming Experiential Archive,” written with Julia Roxanne Wallace in 2016;18 the dynamic catalogs of Janelle Monáe and Me’shell Ndegeocello and Lil Nas X;19 and the visionary Afrofuturism nurtured by adrienne maree brown with Walidah Imarisha and a slate of activist-writers in the collection Octavia’s Brood (2015).20 These imaginative products and others like them must be taken up as dynamic blueprints for a different kind of future— one in which the grand metric for success is thriving among people currently faced with disproportionate struggle.

Bringing these innovations to light is part of how we locate hope. It’s as important as understanding how large social forces make things difficult. More so. A critical perspective that resists the hypnotizing pull of the status quo lets us attend to strength, desire, and love; our pasts, presents, and futures; wisdom, hope, and joy. Especially, the ways they are complex.

Pursuing a Bridge to Thriving

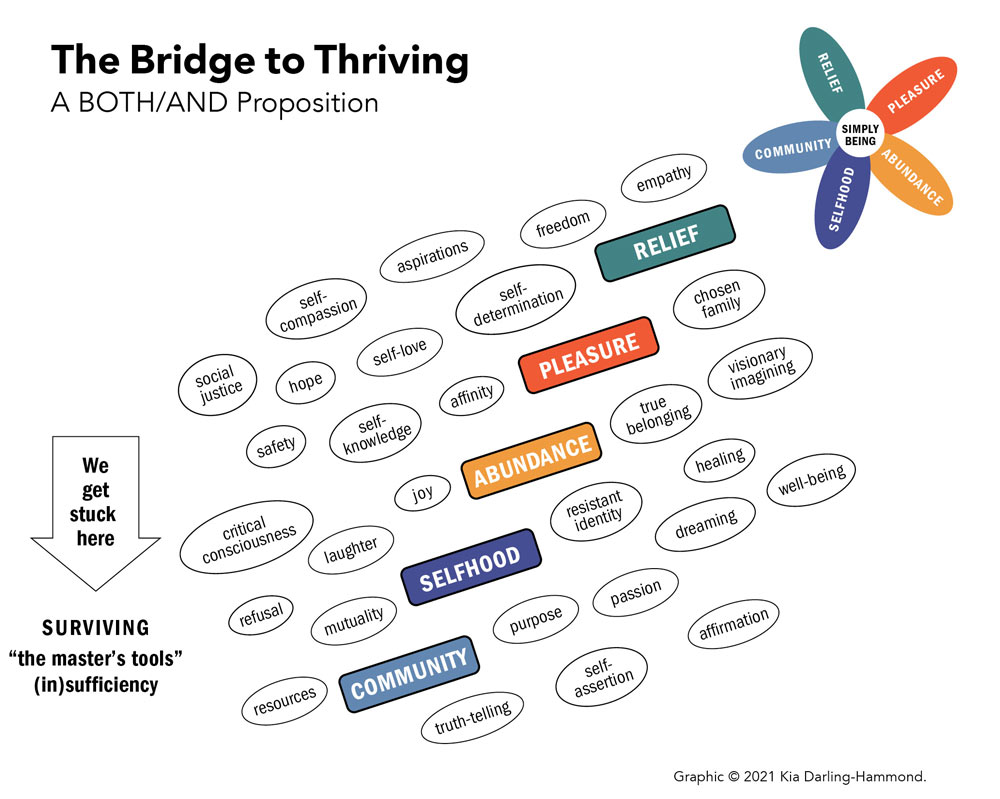

The Bridge to Thriving Framework© (BtTF©), which was born out of conversations with Black LGBTQ+/SGL youth and young adults, explores three big ideas: (1) Surviving Encounters with Oppression, (2) What Thriving Can Be, and (3) What’s on the Bridge to Thriving (i.e., healing, chosen family, etc.).21

Although thriving is not a permanent state of being—and people can thrive in some aspects of their lives more strongly than in others—it is possible to increase one’s capacity for and duration of thriving, and return to it over time. Some of this is on an individual level, but ultimately it is a community- and society-wide project.

Surviving Encounters with Oppression

Violent, oppressive systems shape our lives. The United States imprisons more adults than any other country. In fact, we have numerous states that “lock up more people at higher rates than nearly every other country on earth.”22 Politicians choose cost savings over human safety, as we heard and saw loud and clear in Flint, Michigan. Quieter is that the EPA estimates there are 7.3 million lead pipelines nationwide servicing as many as 10 million homes. According to the CDC, roughly 24 million homes in the nation contain deteriorating lead paint and 4 million of them house small children.23

Almost half of the children in the United States are impacted by adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which can be linked to systems of economic exploitation, patriarchy and the misogyny that shores it up, anti-Blackness, racism, xenophobia, and so on. “One in ten children . . . has experienced three or more ACEs” and are, in many cases, being raised by adults who have themselves experienced adverse childhoods.24 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ACEs resource pagelists such potential long-term effects as autoimmune disease, cancer, pulmonary disease, liver disease, memory disturbances, depression, and more.25 The more ACEs a child experiences, the higher the risk that they will develop a chronic condition later in life. These issues disproportionately impact disabled communities, Native, Black, and immigrant communities, and LGBTQ+/ SGL communities.

Lives are cut short from mental and physical anguish, through accumulated toxic stress resulting in illness, through acute violence at the hands of police and other state and institutional actors, and so on. We are ranked and sorted during our earliest, most impressionable years, internalizing ideas about intelligence, worthiness, rightness, and goodness. We are taught to ignore our needs, including our joy.

Creating the conditions for thriving requires attending to threats to survival—emotional, spiritual, and physical. This can include teaching children how to communicate with adults and authority figures in a way that reduces risk to the young person. It includes learning how to demonstrate “knowledge” in order to have one’s work “taken seriously” or counted. It includes helping people remain attuned to their authentic self and needs, despite the powerful forces encouraging them not to. It requires social justice activism, from marches to lawsuits to boycotts to unionizing.

Researchers26 recommend such individual-level interventions as improving one’s amount and quality of sleep,27 avoiding psychological distress,28 increasing optimism,29 improving self-esteem,30 eating a nutrient-dense diet,31 finding social support,32 and engaging in regular physical activity.33 In fact, high levels of social-emotional support and excellent sleep are particularly powerful. They can protect against and even repair damage caused by toxic stress. Research suggests that when people belong to a community in which their stigmatized identities are celebrated34—where they can find pride in their community’s history, legacies, stories, and triumphs35—they experience a kind of protection from psychological threat, which has physiological implications.

The urgent focus of so many efforts on resilience and survival makes sense. Too many of us don’t survive our encounters with oppression, particularly where complex marginalization is at play. Still, there is more to life; and, as Michael Roberson points out, we have to claim our “divine right to exist.”36

What Is Thriving?

A framework for thriving that centers marginalized communities goes beyond resilience or integration. People experience thriving when they:

- have supportive, affirming communities (particularly affinity community focused on applying critical consciousness to advancing social justice);

- can come to know their true selves, love themselves, and self-assert in a self-determined and empowered way;

- have not just economic stability but also abundant resources for thriving, including time, space, funds, and—crucially—hope, aspirations, and dreams;

- can engage in pleasurable activities (with or without others), pursue their passions, and be joyful; and

- can heal and experience relief from stressors like unsafety, erasure, economic hardship, and social isolation, among others.

In particular, people describe an optimal state of thriving—one in which all five “petals” of the thriving model are activated—as “simply being,” or being able to exist fully and wholly. This requires an ability to know and value oneself, which calls for activation of a resistant identity—one that positions us as central and treasured, not marginal; one that refuses the ways in which the world conspires to make us feel small. Simply being typically happens in the company of a close kinship network, like chosen family; in spaces that feel shielded from unsafety; with the resources of space and time (and sometimes money) available; where the outer world’s stigma and stress are impotent; and where there is joy, pleasure, or even a sense of purpose.

I was getting rid of . . . things that were bringing me down, for sure . . . I would say, yeah, [it was] a time when I was really focused on myself; making concrete steps towards my future . . . I had mental and physical confidence. I had a swagger….. not like, “I’m the shit!” but just, “I am me, and I’m comfortable with my skin.” Some India Arie song or something. It was definitely a swagger: “Pssh. I’m ready to be me. I am me. Boom.”—Marcus37

Possibilities for thriving grow when people are invited to (1) recognize themselves as someone who is entitled to thrive, (2) imagine what their thriving can look like, and (3) receive affirmation and resources to support their vibrant, present and future dreaming and designing. It is immensely helpful to be able to do that with people who believe in one’s thriving possibilities and who honor that each of us, regardless of age, stage, or position, is entitled to exert authority over our lives, needs, and futures.

As people center thriving, they begin to notice the parts of their lives that don’t quite measure up, and make plans to change them. People also begin to name strategies and practices they can (and do) use to advance their thriving—from prioritizing their musicianship, to activism, to changing jobs, to changing partners, and so on.

Sometimes it’s gonna take that courage to be okay with not being the same and not conforming or trying to change yourself.—Sonja38

Finally, people being asked to consider the question of their thriving is powerful. Time and again, people say that they’ve never been invited to really think about it. What make this exercise successful are conditions that allow for deep reflection. Moving through the BtTF© reshapes people’s ideas about themselves, their present, and their future. It is an invitation to consider what constitutes life success—particularly as it is defined and understood by people who are asked to “not be” when offered access to the dominant frameworks for becoming in this world.

Pursuing the Bridge to Thriving is a both/and proposition. It acknowledges the need to pay attention to survival and healing, but urges us to balance that with dreaming in order to advance a visionary remaking of our relationships with one another and our world. Because the systems that confound thriving are so strong, this work begins with a demand. We must believe that thriving is what we deserve, and we have to unapologetically imagine it into existence. The world we need doesn’t yet exist.

***

The Bridge to Thriving is the space between survival/insufficiency and a state of vibrant wholeness. The pathway is not linear and it’s not a one-time journey. Think of the Bridge to Thriving as portable—it can be applied to a variety of projects (building a school, building an office community, building oneself, etc.). It is, essentially, a way to remember what people need in order to flourish.

It is also important to remember that individuals or communities may construct their “bridges” differently. One person may require the time, resources, and space to play music regularly, while another may need to be truly understood by a caring friend. One community may need clean drinking water, while another may need a police oversight commission. Demands may be shared in some contexts and not in others. Ultimately, the bridge invites an analysis of what is needed for access, wholeness, and a life well-lived. Whatever the case, we can be sure that communities are experts regarding what they need to survive, and deserve to exist under conditions that allow them to pause, breathe, dream, and design toward what they need to thrive.

Honestly, I associate thriving a lot with . . . like un-structuring the structure that is society, and government, and all of these things. And thriving, creating abundance around me and for me and for other people. Abundance in that things are taken care of. And that you could be at peace. There is abundance. There’s love and . . . loving connection.—Kat39

As you undertake the work of designing toward thriving, you can ask questions like:

- What healing do I need to do in order to be a trustworthy partner in thriving?

- How do my efforts continuously seek, understand, honor, and amplify the deep wisdom of marginalized communities?

- How do my efforts provide opportunities for relief and pleasure? How do they create conditions that empower others to build lives rich with relief and pleasure?

- What kinds of “selves” are made available to me and the people I coexist with?

- What future possibilities can be imagined?

- How do I hold space for people (including myself) to simply be?

- What practices will make it possible for others to tell me what they truly need?

- How will I intervene against the reproduction of precarity and oppression? How am I complicit or active in its reproduction?

Thriving for me is being able to build up my family, my friends, myself, and our futures, and make sure there is a future to have.—Marcus40

For the sake of ourselves and the seven generations to come, it’s time we work to exceed survival41—to design a visionary, liberated, harmonious future and join together in starting its construction today. The world we need lives in the imaginations and practices of the people our world fails to celebrate. They are worldmakers and waymakers. They weave futures in zines and memes, songs and graffiti. They plot at kitchen tables. They march; they write; they sign; they refuse; they demand. Let’s catch up.

NOTES

- In Kia Darling-Hammond, “To simply be: Thriving as a black queer/same-gender-loving young adult” (PhD , Stanford University, 2018).

- Ibid.

- The Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle, translated and with an introduction by David Ross; revised by L. Ackrill and J. O. Urmson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980); and Omedi Ochieng, “What African Philosophy Can Teach You About the Good Life,” IAI News 68, September 10, 2018, iai.tv/articles/what-african-philosophy-can-teach-you-about-the-good-life-auid-1147.

- Kim M. Blankenship, “A Race, Class, and Gender Analysis of Thriving,” Journal of Social Issues 54, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 393–404; Charles S. Carver, “Resilience and Thriving: Issues, Models, and Linkages,” Journal of Social Issues 54, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 245–66; Corey L. M. Keyes and Jonathan Haidt, eds., Flourishing: Positive Psychology and the Life Well-Lived (Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2002); Laura M. Padilla-Walker and Larry J. Nelson, Flourishing in Emerging Adulthood: Positive Development During the Third Decade of Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017); Sarah Reed and Robin Lin Miller, “Thriving and Adapting: Resilience, Sense of Community, and Syndemics among Young Black Gay and Bisexual Men,” American Journal of Community Psychology 57, no. 1–2 (March 2016): 129–43; Carol D. Ryff and Burton H. Singer, “Know Thyself and Become What You Are: A Eudaimonic Approach to Psychological Well-Being,” Journal of Happiness Studies 9, no. 1 (January 2008): 13–39; and Martin E. P. Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, “Positive psychology: An introduction,” The American Psychologist 55, no. 1 (2000): 5–14.

- Eve Tuck, “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities,” Harvard Educational Review 79, 3 (Fall 2009): 409–28.

- Keyes and Haidt, Flourishing. And see Martin P. Seligman, “Foreword: The Past and Future of Positive Psychology,” in Flourishing, xi–xx.

- Edward Brockenbrough, personal communication with the author, April 23,

- Darling-Hammond, “To simply be.”

- Laurence Kirmayer et al., “Community Resilience: Models, Metaphors and Measures,” Journal of Aboriginal Health 5, no. 1 (2009): 62–117.

- Ibid., 78–79.

- Darling-Hammond, “To simply be.”

- L. H. Stallings, “Hip Hop and the Black Ratchet Imagination,” Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Gender, and the Black International 2, no. 2 (2013): 135–39.

- Bettina Love, “A Ratchet Lens: Black Queer Youth, Agency, Hip Hop, and the Black Ratchet Imagination,” Educational Researcher 46, no. 9 (December 2017): 539–47.

- W. J. Weatherby, James Baldwin: Artist on Fire, A Portrait (New York: D.I. Fine, 1989).

- Ehn Nothing, Marsha Johnson, and Sylvia Rivera, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer Antagonistic Struggle (Bloomington, IN: Untorelli Press, 2013).

- Marlon Bailey, “Performance as Intravention: Ballroom Culture and the Politics of HIV/AIDS in Detroit, Souls 11, no. 3 (July–September 2009): 253–74; and Marlon M. Bailey, “Engendering space: Ballroom culture and the spatial practice of possibility in Detroit,” Gender, Place & Culture 21, no. 4 (2014): 489–507.

- Michael Roberson on the Ballroom Freedom School, interview, ArtsEverywhere, September 10, 2016, video, 13:00, at 06:30, com/216007645.

- Alexis Pauline Gumbs and Julia Roxanne Wallace, “Something Else to Be: Generations of Black Queer Brilliance and the Mobile Homecoming Experiential Archive,” in No Tea, No Shade: New Writings in Black Queer Studies, ed. E. Patrick Johnson (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016): 380–94.

- Jon Dolan, “Lil Nas X Makes Us Like Him Even More on ‘Montero,’” Rolling Stone, September 17, 2021, com/music/music-album-reviews/lil-nas-x-montero-1226841/; Larry Nichols, “Running for Covers: Meshell Ndegeocello talks inspiration for new album,” Philadelphia Gay News, March 22, 2018, epgn.com/2018/03/22/running-for-covers-meshell-ndegeocello-talks-inspiration-for-new-album/; and Brittany Spanos, “Janelle Monáe Frees Herself,” Rolling Stone, April 26, 2018, rollingstone.com/music/music-features/janelle-monae-frees-herself-629204/.

- Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown, , Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2015).

- DrKiaDH (Kia Darling-Hammond), “Bridge to Thriving Framework,” Wise Chipmunk, February 25, 2021, com/2021/02/25/the-bridge-to-thriving-framework/.

- Emily Widra and Tiana Herring, “States of Incarceration: The Global Context, 2021,” Prison Policy Initiative, September 2021, org/global/2021.html.

- “Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed December 23, 2021, cdc.gov/nceh/lead/prevention/sources/paint.htm; and Alison Young, “Got lead in your water? It’s not easy to find out,” USA Today, March 16, 2016, www.usatoday.com/story/news/2016/03/16/testing-assessing-safety-of-drinking-water-lead-testing-assessing-safety-of-drinking-water-lead-contamination/80504058/.

- Vanessa Sacks and David Murphey, “The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, nationally, by state, and by race or ethnicity,” Child Trends, February 12, 2018, org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity.

- “Adverse Childhood Experiences Resources,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed December 3, 2021, gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/journal.html.

- See for example Irene Christodoulou, “Reversing the Allostatic Load,” International Journal of Health Science 3, 3 (July–September 2010): 331–32.

- Ilia Karatsoreos and Bruce S. McEwen, “Psychobiological allostasis: resistance, resilience and vulnerability,” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 15, no. 12 (December 2011): 576–84.

- Bruce McEwen and Peter J. Gianaros, “Stress- and Allostasis-Induced Brain Plasticity,” Annual Review of Medicine 62 (2011): 431–45.

- Bruce McEwen, “Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators: central role of the brain,” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 8, no. 4 (December 2006): 367–81.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- McEwen and Gianaros, “Stress- and Allostasis-Induced Brain Plasticity.”

- Ibid.

- Kathleen Bogart, Emily M. Lund, and Adena Rottenstein, “Disability pride protects self-esteem through the rejection-identification model,” Rehabilitation Psychology 63, no. 1 (February 2018): 155–59.

- William Bannon et al., “Cultural Pride Reinforcement as a Dimension of Racial Socialization Protective of Urban African American Child Anxiety,” Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Human Services 90, no. 1 (January 2009): 79–86.

- ArtsEverywhere, Michael Roberson on the Ballroom Freedom School.

- Darling-Hammond, “To simply be.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Values,” Haudenosaunee Confederacy, accessed December 3, 2021, haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/values/.

0 Commentaires