This article is, with publisher permission, adapted from a more extensive journal article, “A Tax Credit Proposal for Profit Moderation and Social Mission Maximization in Long-Term Residential Care Businesses” published last year by Nonprofit Policy Forum.

For decades, for-profit nursing homes and assisted living facilities have seen profit maximization overrun social mission. The result has been the neglect—or even abuse—of the frail and elderly, a situation that became patently clear amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Even though companies are funded through public Medicaid and Medicare dollars, patients receive little protection.

Fortunately, existing policy tools can address this. Specifically, we propose using federal tax credits, combined with Medicare and Medicaid dollars, to restructure the ownership and financing of the nursing care industry. By making federal payment contingent on partial employee and impact investor ownership, limiting the use of complex organizational structures, and sweetening the deal with tax credit incentives, we believe the federal government can restore the alignment of the nursing care and assisted living industries with a social mission of providing patients with top-quality care.

Understanding the Unacceptable Status Quo

Numerous studies demonstrate that for-profit senior care facilities show higher rates of neglect and abuse when compared with similar nonprofit entities (Comondore et al. 2009). These statistics hold true across time and national boundaries (Brennan et al. 2012) and demonstrate the failure of government regulations to rein in abuses (Coskun 2022; Silver-Greenberg and Gebeloff 2021). Moreover, the for-profit service quality gap worsens when private equity intersects with complex corporate structures. A rigorous study shows that private equity ownership of long-term care facilities increases the short-term mortality of Medicare patients by 10 percent (Gupta et al. 2021).

Today, 70 percent of US nursing home providers are for-profit businesses (Goldstein, Silver-Greenbergand, and Gebeloff 2020; Lendon et al. 2019). While one approach might be to shift provision back to nonprofits entirely, we suggest a middle-of-the-road intervention that makes skilled caregivers co-owners and incentivizes for-profit providers to maximize their social mission through a tax credit mechanism.

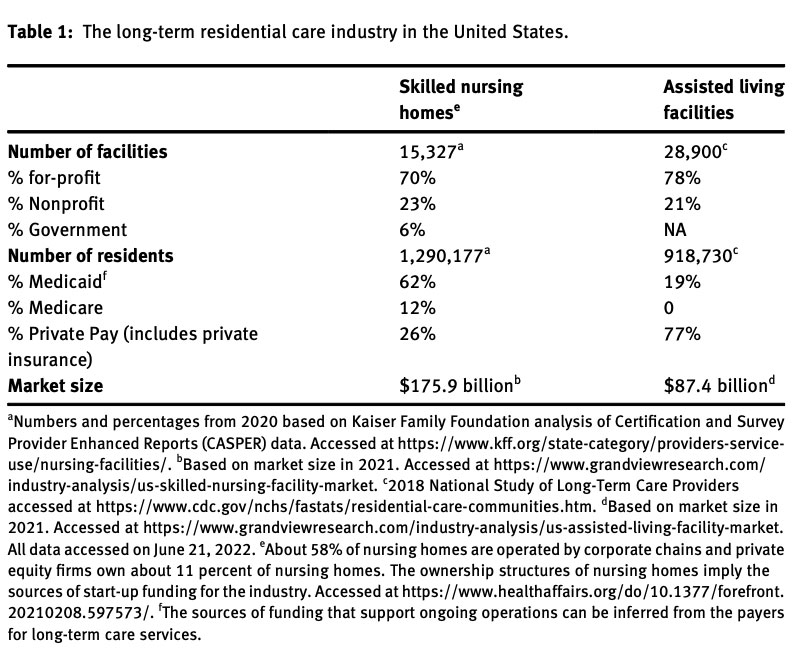

US long-term care businesses (see Table 1) often operate under conditions where they have an extreme information advantage over their customers. This is because those who pay for services are not typically the people directly receiving the services (Chou 2002). As a result, the buyer often unknowingly purchases poor-quality services for a vulnerable individual who is typically unable to communicate service shortfalls. We posit that an antidote to this situation is to rein in profit maximization that benefits private investors.

A table documenting the scale and the scope of the $250-billion industry is below:

Our proposed policy solution is to create a tax credit contingent on changing the ownership and financing structure of the industry. It not only rewires the incentives away from profit maximation to profit moderation but the subsidy from the federal tax credit also provides extra liquidity to financially stressed nursing homes. In this manner, it becomes possible to root out many ills in the system.

We envision that, after a window where alignment with abiding by the tax credit provision is voluntary or only required if facilities are failing on quality measures, Medicare and Medicaid could phase in a requirement that businesses wanting to receive federal dollars abide by its provisions (Coskun 2022).

Policy Design

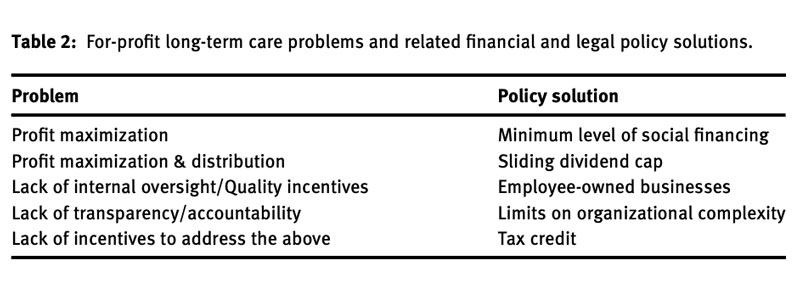

Table 2 below outlines the problems that for-profit nursing homes and assisted living currently face and our proposed financial and legal policy solutions:

We propose a tax credit that would have four provisions tied to it to address the four problems outlined above. The first provision requires that a minimum percentage of investments in the for-profit come from socially minded funds (social impact bonds and impact investing); this is done to put the social return on investment on equal terms with the economic return (Lohr 2021). The second creates a sliding dividend cap that adjusts with the amount of social investment. The third stipulates that long-term care businesses must have at least partial employee ownership. A fourth provision would place strict limits on the use of complex corporate structures that make it difficult to identify who owns the care facility when there are service quality issues (Kahn 2018). We flesh out each below.

Changing the Structure of Care Finance

To redirect profit in long-term care facilities and increase accountability, the tax credit law would require that a minimum percentage of ownership in the for-profit long-term care business come from social financing through providing initial capital or buying out conventional financial return-seeking investors. This helps ensure that investor pressure for social returns balances out financial pressures. Here, by social financing, we refer primarily to impact investing and social impact bonds (Geobey and Harji 2014; Han, Chen, and Toepler 2020; Rosenman 2019).

Impact investing, as defined by the Global Impact Investing Network, is an investment tool “made with the intention to generate positive, measurable, social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.” This means that investors put their money behind businesses trying to provide quality products or services and address societal problems. Regulatory policy, tied to long-term care agreements with impact investment funds, can contractually require that certain health and social care standards are met, thereby helping ensure the vulnerable elderly population receives the quality care that is largely being paid for by taxpayer money.

Second, Social Impact Bonds help organizations raise funds for socially oriented projects from the backing of private, public, and/or investors interested in philanthropy (Joy and Shields 2013). Admittedly, they are relatively new (Crowley 2014; Katz et al. 2018). Between 2010 and 2019, 138 SIBs accounting for $441 million in capital have been issued globally, ranging in causes from workforce development to education and medical services (Hulse, Atun, and McPake 2021).

SIBs have their drawbacks. For example, because SIBs depend on buy-in from private investors, SIBs may empower private investors to promote social changes that don’t correspond with the public interest (Child, Gibbs, and Rowley 2016). Nonetheless, we believe that impact investing and SIBs, shifting investor pressures toward accountability, would help improve social outcomes.

A Sliding Dividend Cap

A second provision that we recommend is a sliding dividend cap. The cap would limit profit distribution based on a sliding scale dependent on the level of social investment made in the long-term care business. For example, if social financing equaled 20 percent of overall capital investment, profit distribution to the remaining 80 percent representing regular investors would be capped at 40 percent.

On the other hand, if social investments only equaled 15 percent of overall investment, then the distribution of profit to investors representing the remaining 85 percent would be capped at 35 percent. Therefore, the greater the amount of social financing in the investment mix, the greater the payments that can be distributed to regular investors.

While the sliding dividend cap relative to social financing is a newly proposed policy idea, static dividend caps on investments are not new and have been implemented in many countries (Liao, Tawfik, and Teichreb 2019). A dividend cap has been in use the longest and most prominently as a component of the Community Interest Company established in 2005 in the United Kingdom, providing an opportunity to examine the use of this policy tool.

Prioritizing Employee Ownership

Also tied to the tax credit would be a requirement to use an employee-ownership business structure. This would help create internal checks and balances to ward off poor service quality. Employee-owned businesses are a tested solution in this area, especially the Employee Stock Ownership Plan, or ESOP, housed in S and C corporations.

Established in 1974 to encourage businesses to share wealth with employees, an ESOP is essentially a company-funded retirement plan whereby the company contributes or provides debt-purchased shares on behalf of its employees (Hricko and Starr 2014). Businesses are incentivized through tax benefits; the most generous of which accrue to ESOPs in S corporations, which “do not have to pay tax on profits attributable to the percentage of the company’s ownership in the ESOP. For example, a 30-percent ESOP avoids tax on 30 percent of the profits” (Hricko and Starr 2014, 67). Also important, an employee’s shares are subject to vesting, such that the longer employees work, the more shares they accumulate, with full vesting required at no later than six years of employment (Hricko and Starr 2014).

Research on ESOPs has shown that employees in such companies are more motivated and have higher retention rates than workers at investor-owned companies (Hricko and Starr 2014; Jenkins and Chivers 2022; Josephs 2021). When closely held, ESOP companies perform well across a range of other benefits for employees and company performance (NCEO 2018). Of interest to investors, ESOPs see a per year 2.5 percent increase in sales, employment, and productivity growth relative to what otherwise would have been expected (Hricko and Starr 2014).

ESOPs also provide workers with important governance rights. Among these, in private companies, ESOP participants must be able to direct the trustee on the voting of allocated shares for sale of all or substantially all the company’s assets, merger, liquidation, recapitalization, reclassification, dissolution, or consolidation (NCEO 2012).

Shareholders of existing long-term care facilities could benefit from a transition to the ESOP structure in several ways, including deferment or elimination of capital gains taxes, corporate tax savings, greater cash flow, and more motivated employees (Hricko and Starr 2014).

Compelling Accountability

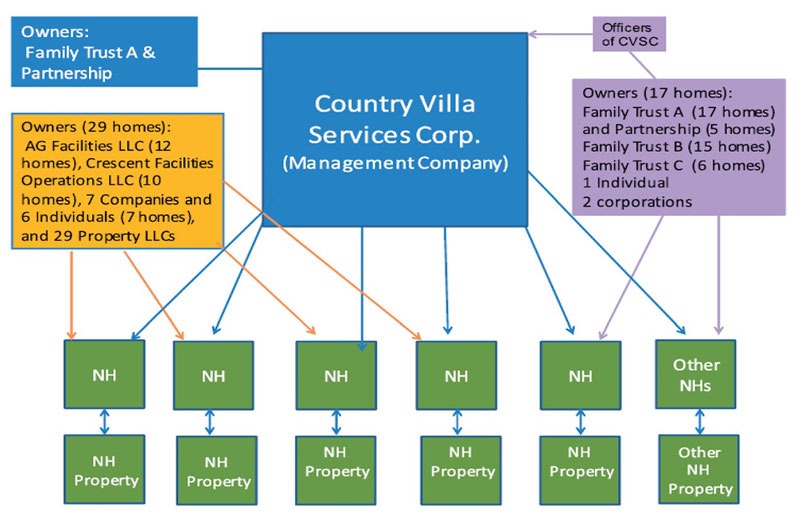

A fourth key provision we propose is to restrict the use of complex corporate structures that shield many for-profit long-term care facilities from accountability. The literature on corporate structures concerning poor nursing home service quality implicates three features that are often found together: multi-layer shareholding, related party transactions, and chain ownership. We propose limits on all three.

First, multi-layer shareholding makes the chain of accountability longer and harder to hold investors of nursing homes accountable (Kahn 2018). It is defined as ownership that cannot be traced back to natural-person shareholders or beneficial owners within a couple of layers (IDB and OECD 2019). Harrington, Ross, and Kang (2015) conducted a case study of a California nursing home chain and found that complex, interlocking individual and corporate owners and property companies obscured its ownership structure and financial arrangements (see Figure 1).

Second, closely tied to private equity are related-party transactions found in three-quarters of nursing homes—more than 11,000—in the US (Rau 2018). Such transactions between related parties—for example, between a holding company and subsidiary companies that share a common holding company or shareholders (SEC 2017)—can easily be abused. Compounded by loose disclosure rules, this practice often results in nursing homes being underfunded—leading to understaffing, a shortage of essential supplies, and injuries to residents (Duhigg 2007).

Third, chain ownership is also linked to poor service quality. Grabowski et al. (2016), studying nursing home data from 1993 to 2010, found that nursing homes in chains of all sizes had many more deficiencies than independent nursing homes did and that low-quality nursing homes were targeted by chains for acquisition.

The combination of private equity and chain ownership is particularly toxic. A study by Harrington et al. (2017) of the five largest for-profit nursing home chains in five countries (Canada, Norway, Sweden, United Kingdom, and the United States) finds that private equity investors increasingly own large for-profit nursing home chains, have had many ownership changes over time, and have complex organizational structures. These chains have high profit margins and often have documented quality problems (Burns et al. 2016; Grabowski et al. 2016).

Tax Credit Structure

The term “tax credit” under the US taxation system is defined as direct forgiveness of tax owed by the taxpayer, which “reduces tax liability by an amount exactly equal to the credit” (Mikesell 2016). A tax credit is a suitable policy tool to encourage the socially responsible operation of for-profit long-term care facilities. It does so at a public cost that is lower than with tax-exempt nonprofits, which are exempt from corporate income tax on all mission-related activity. Using a tax credit policy also avoids the need to establish a new government agency to administer the policy (Howard 2002).

The sliding scale feature of the policy design can be realized structurally in the tax credit with sliding tax bases and rates; in other words, a firm with greater social ownership would qualify for a greater credit amount. Since one of the goals of having the credit is to lower financial pressures on nursing homes to cut corners on care, it should also be refundable. That is, if, due to low earnings, the tax owed is less than the value of the tax credit, they would receive the difference as a rebate.

That said, there are still several potential obstacles with implementation—the most serious of which is the possibility of gaming the system. Just as nonprofits may sign contracts that benefit related parties and thereby evade regulation, tax credit recipients may engage in similar evasions. Nonetheless, we believe that, on balance, the policy design offered here could improve nursing care quality for millions of Americans.

Putting Care at the Center of Federal Nursing Home Policy

As noted, long-term residential care businesses today maximize profits, often at the expense of vulnerable individuals. We identified four major issues that work to maintain this situation and propose four policy ideas to address them—all of which would be anchored by the purchasing power of Medicare and Medicaid, and our proposed tax credit.

First, we propose that nursing homes be required to obtain a minimum percentage of social financing. Second, we recommend implementing a sliding dividend cap that ties the payouts received by non-impact investors to the business’ success at acquiring impact investment financing. Third, we recommend adding a requirement to use an ESOP or similar structure to provide partial employee ownership, thereby increasing workers’ ability to hold nursing homes accountable. Fourth, we propose limits on complex corporate structures that keep ownership hidden and reduce accountability.

To achieve the intended improvement in the quality of care for residents in these facilities, these policy components need to work together. Since most of these policy tools have not been used extensively in the long-term care industry, pilot projects are needed to test the various policy components, perhaps first in a state-level program. We suggest that a program evaluation component be included in pilots to accumulate empirical knowledge.

Eventually, a well-thought-out and locally tested “social responsibility in long-term residential care tax credit” bill could be proposed in Congress. We believe such an approach could be applicable in other fields where businesses share similar characteristics, such as the for-profit provision of care for vulnerable individuals. These include for-profit hospices, childcare centers, and group homes for youth and individuals with disabilities, among others.

The fact of the matter is: our current system of nursing homes and assisted living care is broken, costing thousands of people their lives each year. The government can and must act to restore a social mission of providing patients with top-quality care. The need is clear.

References

Brennan, D., B. Cass, S. Himmelweit, and M. Szebehely. 2012. “The Marketisation of Care: Rationales and Consequences in Nordic and Liberal Care Regimes.” Journal of European Social Policy 22 (4): 377–91.

Burns, D., L. Cowie, J. Earle, P. Folkman, J. Froud, P. Hyde, S. Johal, I. R. Jones, A. Killett, and K. Williams. 2016. “Where Does the Money Go? Financialised Chains and the Crisis in Residential Care.” In CRESC Public Interest Report.

Child, C., B. G. Gibbs, and K. J. Rowley. 2016. “Paying for Success: An Appraisal of Social Impact Bonds.” Global Economic Management Review 21: 36–45.

Chou, S. 2002. “Asymmetric Information, Ownership and Quality of Care: An Empirical Analysis of Nursing Homes.” Journal of Health Economics 21 (2): 293–311.

Comondore, V. R., P. J. Devereaux, Q. Zhou, S. B. Stone, J. W. Busse, N. Ravindran, K. E. Burns, T. Haines, B. Stringer, D. Cook, S. D. Walter, T. Sullivan, O. Berwanger, M. Bhandari, S. Banglawala, J. N. Lavis, B. Petrisor, H. Schünemann, K. Walsh, N. Bhatnagar, and G. H. Guyatt. 2009. “Quality of Care in For-Profit and Not-For-Profit Nursing Homes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” British Medical Journal 339.

Coskun, M. E. 2022. “A Quantitative Analysis of Ownership Induced Quality Gaps in the Long-Term Care Sector: Influences of Ownership Conversions, Self-Reporting, Regulatory Reforms, and COVID-19.” PhD diss., Georgia State University.

Crowley, D. M. 2014. “The Role of Social Impact Bonds in Pediatric Health Care.” Pediatrics 134 (2): e331–3.

Duhigg, C. 2007. “At Many Homes, More Profit and Less Nursing.” New York Times, September 23.

Geobey, S., and K. Harji. 2014. “Social Finance in North America.” Global Social Policy 14 (2): 74–277.

Goldstein, M., J. Silver-Greenbergand, and R. Gebeloff. 2020. “Push for Profits Left Nursing Homes Struggling to Provide Care.” New York Times, May 7.

Grabowski, D. C., R. A. Hirth, O. Intrator, Y. Li, J. Richardson, D. G. Stevenson, Q. Zheng, and J. Banaszak-Holl. 2016. “Low-Quality Nursing Homes Were More Likely Than Other Nursing Homes to be Bought or Sold by Chains in 1993–2010.” Health Affairs 35 (5): 907–14.

Gupta, A., S. T. Howell, C. Yannelis, and A. Gupta. 2021. “Does Private Equity Investment in Healthcare Benefit Patients? Evidence from Nursing Homes.” In NBER Working Paper Series. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Han, J., W. Chen, and S. Toepler. 2020. “Social Finance for Nonprofits: Impact Investing, Social Impact Bonds, and Crowdfunding.” In Routledge Companion to Nonprofit Management, edited by H. K. Anheier, and S. Toepler, 482–93. London: Routledge.

Harrington, C., F. F. Jacobsen, J. Panos, A. Pollock, S. Sutaria, and M. Szebehely. 2017. “Marketization in Long-Term Care: A Cross-Country Comparison of Large For-Profit Nursing Home Chains.” Health Services Insights 10: 1–23.

Howard, C. 2002. “Tax Expenditures.” In The Tools of Government: A Guide to the New Governance, edited by L. Salamon, 410–444. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hricko, M. J., and I. Starr. 2014. “Private Equity and ESOPs: A Creative Combination.” In Staying Private: Liquidity Options for Entrepreneurial Companies, edited by A. El-Tahch, R. Gandre, M. J. Hricko, C. Rosen, K. Sawyer, and I. Starr, 63–74. Oakland, CA: National Center for Employee Ownership.

Hulse, E. S. G., R. Atun, B. McPake, and J. T. Lee. 2021. “Use of Social Impact Bonds in Financing Health Systems Responses to Non-Communicable Diseases: Scoping Review.” BMJ Global Health 6 (3).

IDB and OECD. 2019. A Beneficial Ownership Implementation Toolkit. Washington, D.C.: Inter-American Development Bank.

Jenkins, S., and W. Chivers. 2022. “Can Cooperatives/Employee-Owned Businesses Improve ‘Bad’ Jobs? Evaluating Job Quality in Three Low-Paid Sectors.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 60: 511–35.

Josephs, M. 2021. “How PE Firms are Embracing Employee Ownership.” The Middle Market, March 3.

Kahn, K. 2018. “When Profit Is the Motive Nursing Home Care Suffers,” NPQ, January 8.

Lendon, J. P., M. Sengupta M, V. Rome, C. Caffrey, L. Harris-Kojetin, and A. Melekin. 2019. “Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States—State estimates supplement.” National Study of Long-Term Care Providers.

Liao, C., E. U. Tawfik, and P. Teichreb. 2019. “The Global Social Enterprise Lawmaking Phenomenon: State Initiatives on Purpose, Capital, and Taxation.” The Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 36: 84–114.

Lohr, S. 2021. “Job Training That’s Free Until You’re Hired Is a Blueprint for Biden.” New York Times, April 7.

Mikesell, J. 2016. Fiscal Administration, 10th ed, 432–4. Boston: Cengage Learning.

NCEO. 2012. The Rights of ESOP Participants. Oakland, CA: National Center on Employee Ownership, April 5, https://www.nceo.org/articles/rights-esop-participants.

NCEO. 2018. Research on Employee Ownership, Corporate Performance, and Employee Compensation. Oakland, CA: National Center on Employee Ownership.

Rau, J. 2018. “Care Suffers as More Nursing Homes Feed Money into Corporate Webs.” New York Times, January 22.

Rosenman, E. 2019. “The Geographies of Social Finance: Poverty Regulation through the ‘Invisible Heart’ of Markets.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (1): 141–62.

SEC. 2017. Advanced Credit Technologies, Inc. Related Party Transactions Policy.

Silver-Greenberg, J., and R. Gebeloff. 2021. “How U.S. Ratings of Nursing Homes Mislead the Public.” New York Times, March 13.

0 Commentaires