This is the second installment of a five-part series, Reclaiming Control: The History and Future of Choice in Our Health, examining how healthcare in the US has been built on the principle of imposing control over body, mind, and expression. However, that legacy stands alongside another: that of organizers, healers, and care workers reclaiming control over health at both the individual and systems levels. Published in five monthly installments from July to November 2022, this series aims to spark imagination amongst NPQ‘s readers and practitioners by speaking to both histories, combining research with examples of health liberation efforts.

The stories always surface—at first tentatively, and then in an outpouring of deep frustration—at backyard barbecues, in clinic waiting rooms, during community workshops. Over the past 16 years, in my work as a patient advocate, health scholar, and public health official, I’ve had a front row seat to friends, coworkers, clients, and constituents sharing their experiences of harm at the hands of the healthcare system.

Once, at a neighborhood association meeting, a resident shared with me that her world had become a series of endless phone calls after her father was diagnosed with a terminal illness. In between working two jobs, she was trying to enroll him in health insurance, sort through stacks of bills from medical debt collectors, intervene with a clinician who refused to prescribe her father pain medication, assess whether joining a new pharmaceutical trial was worth the risk, and on and on—all the while caring for her father and managing her own grief.

Many of us have worked to heal ourselves, whether from an acute illness or the trauma of oppressive systems, and have encountered along the way obstacles that stand in the way of that healing. It’s no surprise that people who recount their negative healthcare experiences are frequently met with understanding and acknowledgement from their audience—within these stories, many express a desire to better control how health is defined, delivered, paid for, and much more.

And yet, while we may share the feeling that something isn’t right, why—even among those who have dedicated their lives and careers to promoting health—is it still unclear how to translate that feeling into action? What would it look like for these collective experiences to connect to a broader power-building strategy that illuminates clear pathways for change?

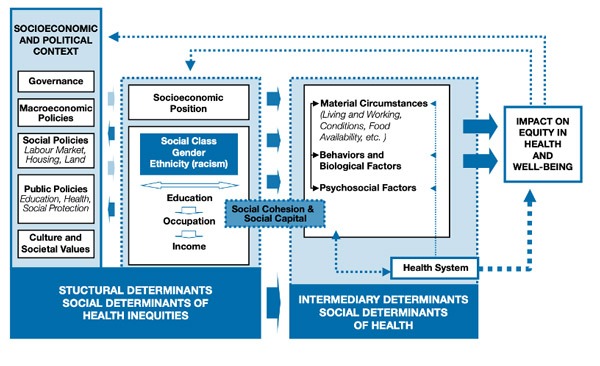

Social movements have long used frameworks that center people’s right to live healthy, whole lives, particularly when it comes to physical and economic freedom. Even when organizing campaigns are not explicitly focused on health as a direct outcome they seek to impact, they still connect to a broader framework of holistic well-being, for “health” is a complicated, multi-layered thing shaped by social determinants of health (SDH). As the image below illustrates, these determinants include everything from where we live, to our identities and the policies and values that undergird our society.

Figure 1: World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health Framework

As a result, organizing for fair wages, securing greater environmental protections, and expanding rights for historically oppressed groups all have the potential to impact health.

Activism and the Fight for Health Justice

Social justice organizers have long centered health as a core value within their work. During the civil rights movement, health as a human right was a core tenet of the Black Panther Party’s political philosophy. In response to the insufficiency—and, in many cases, outright discrimination and violence—of existing healthcare structures, the Black Panthers built free clinics that were the precursors to community health centers, which to this day disproportionately serve low-income and BIPOC communities.

In the 1980s, the Aids Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) leveraged the collective power of LGBTQ+ activists and their allies to demand the federal government acknowledge the AIDS epidemic and fund research, treatment, healthcare facilities, and more. Through protests, political base-building, relational strategy with agency officials at the US Department of Health and Human Services, and many other tactics, ACT UP shifted the standard of care across the sector.

Of course, the movement for reproductive justice also has a rich and complex history. In the early 1990s, activist women of color defined reproductive justice using an intersectional framework—addressing race, gender, ability, sexuality, and more—that centered their experiences and perspectives. Throughout much of the 20th century, the movement for reproductive rights, dominated by white women, used the paradigm of choice, which ignored the social systems and structural factors that shape access to choices in the first place. For example, in this context, even legal access to abortion was an insufficient guarantee that queer, disabled, low-income, and transgender people, among others, would be able to access care—let alone exercise full control over their bodies.

The efforts of activist women of color were driven by a desire to reclaim bodily autonomy from systems that have long sought to control the bodies, minds, and voices of oppressed peoples. Yet, despite paradigm-shifting victories, we now find ourselves in a dire moment when many of the rights secured over the past few decades are being stripped away.

Organizing for the Power to Design Health

Against this backdrop, many communities are exploring what it would look like to plug into a broader power building movement that targets the various branches of the healthcare industry that continue to control people’s bodies. Starting at the local level, the hospital often serves as the most visible proxy for the uncertainties of healthcare. While for many it is an institution entrusted with tending to us during life’s milestones and emergencies, for many others it is a potential source of community disempowerment and displacement.

A participatory action research project between the Coalition to Save and Transform Interfaith, Community Care Brooklyn, and the MIT Community Innovators Lab explores this complex relationship between a community and its local hospital in an online case study that traces the coalition’s efforts between 2013 and 2019 to keep the Interfaith Medical Center, a safety net hospital in Brooklyn, open.

Challenges with Medicaid reimbursement and financial mismanagement in the early 2010s had led to the closure of several hospitals in New York City, including four Brooklyn-based hospitals, which were specifically designed to serve the uninsured, Medicaid enrollees, and other marginalized patients. After an announcement in 2013 that Interfaith would be filing for bankruptcy and closing—which would also have resulted in the loss of more than 1500 local jobs—two local unions, 1199SEIU and the New York State Nurses’ Association, mobilized.

Organizers focused not only on preventing the hospital’s closure, but also on fundamentally changing the power dynamic between Interfaith and community members. Leveraging the unions’ deep and historic civic infrastructure, the coalition deployed a multi-pronged strategy that included protests, policy influence, coalition-building with various Brooklyn constituencies, and engaging with a complex web of state Medicaid programs to ultimately keep Interfaith open via integration with Community Care Brooklyn, a coordinated care network run by neighboring health system Maimonides Medical Center.

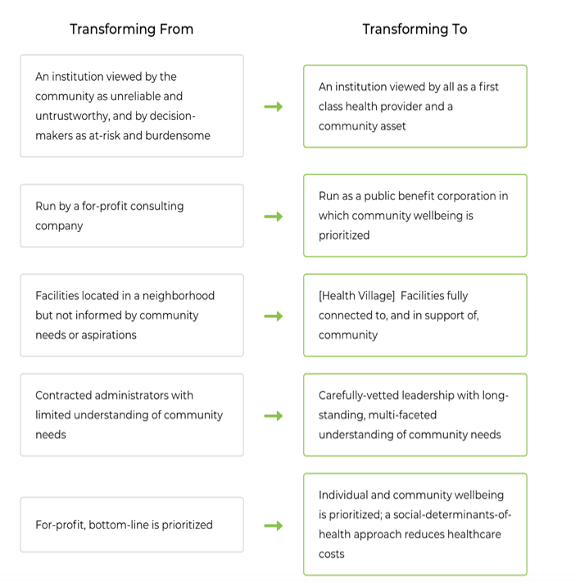

These victorious community power building methods translated into additional decision-making power: the coalition secured a role in selecting the new Interfaith CEO and engaged in collective visioning for the hospital’s new direction, as captured in the visual below:

Figure 2: Notes from Coalition to Save and Transform Interfaith community meeting

This example points to the transformative effect that organized community power can have at the local level, even against a backdrop of complex state- and federal-level health policies that frequently harm BIPOC and low-income communities.

One of our most complicated policy albatrosses is health insurance and coverage: without a guaranteed right to healthcare, and given continued organized resistance to the idea of a single-payer system, Medicaid and Medicare access is largely decided at the state level, where dated, biased views on who “deserves” access to healthcare abound.

In Colorado, as in many other states, this has resulted in a policy landscape in which—even after Medicaid expansion was adopted by the state in 2013—undocumented families and other marginalized communities are ineligible for coverage. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted BIPOC communities most severely, insurance inequity further deepened immigrant families’ burden when accessing care and treatment.

The Colorado-based Center for Health Progress (CHP), a community power-building organization that works across the state to fight for immigrant health and other issues, assembled its diverse, state-wide membership along with coalition partners to secure the passage of a bill, HB22-1289, that will ensure that pregnant, undocumented immigrants and their children are eligible for Medicaid.

The organization engaged grassroots leaders across the state, including first-generation immigrants, native Spanish speakers, and allied health professionals, among others, to craft a legislative point of view rooted in community members’ lived experiences. Joe Sammen, CHP’s Executive Director, highlighted the campaign’s structure, saying “That push for coverage came from the base, from conversations we had with members about what was most impacting their lives.”

Building on their legislative victory, CHP is now further building its base, conducting one-on-one conversations in its key communities in order to build an analysis of power that centers the needs and aspirations of the organization’s members. Through its Nuestra Salud, Nuestra Communidad campaign in Fort Morgan, CO, for example, the organization is engaging community members around the concepts that 1) healthcare is more than just medical care; 2) the health care system is not meeting the needs of the community; 3) working collectively creates the power to enact change. “Universal coverage is one broader piece of holding the healthcare system accountable,” explains Sammen.

Organizations at the national level are also exploring what it looks like to build power to hold healthcare institutions accountable. Shift Health Accelerator, a nationwide distributed leadership network of grassroots community health leaders, is exploring the role of community-centered, participatory decision making in both how health success is defined and how healthcare capital flows into those local visions.

Shift works with several leaders who are making the case for healing justice work—from the creation of holistic green spaces to the provision of community-based trauma-informed care and beyond—amongst other initiatives, as a core component of what healthcare institutions should be funding and supporting. Bringing together their constituents to develop community standards for healthcare evidence, evaluation, data ownership, and accountability, these leaders are working with community partners to push back on dominant healthcare standards that deprioritize lived experience.

“To move the needle on the structural factors that shape health, healthcare institutions must invest in the solutions that experts on the ground are developing,” says Lisa Richardson, a member of the Shift leadership team. “Historically, community leaders have been locked out of decisions about how healthcare institutions tackle the social determinants of health for the people they serve.”

Community members with lived experience of health inequities are rarely in decision-making positions with respect to healthcare funding, despite the public dollars flowing through the system. Earlier this year, Shift piloted a Collaborative Fund that placed funding from a health foundation into the hands of several community-based organizations, which then developed a customized, nuts-to-bolts approach to deploying those dollars. The lessons learned from this process demonstrate what democratized approaches to health funding decisions can look like.

While the concepts of participatory grantmaking and collaborative decision-making aren’t new, they are still rare in the context of health. As someone who has worked on community-based health initiatives for more than 25 years, Richardson shares, “This is the first time I have had the opportunity to work with peer leaders in such a generative space. Cross-movement work is the foundation of building power and creating a world where everyone can thrive.”

Constructing a Foundational Analysis for Future Efforts

These examples all present exciting opportunities for the field, despite the challenges inherent in building a broader base to reclaim control of healthcare. The sprawling and technical nature of healthcare, for example, can be frustrating for base-building organizations. What is the correct power analysis with the right set of targets to focus on when payers, providers, pharmaceuticals, and the rest of the massive healthcare sector are so deeply intertwined?

For example, a grassroots organization seeking to ensure that federal dollars allocated for mental health services are directed into community-based, culturally-rooted practices rather than mainstream (often white-led) clinical programs, might find that the people who decide where funding goes occupy multiple levels: they include federal policymakers engaged in legislative action, state Medicaid offices setting rules, and local hospitals that distribute funds through their grantmaking programs, to name just a few. Each of these scenarios requires distinct analyses, strategies, and entry points in order to achieve community oversight, which can be a challenge for resource-constrained organizations with limited lines of sight into the workings of these often-opaque institutions.

The commodification of healthcare also undergirds this confusing structure. Healthcare institutions frequently possess mission-based strategies, and many are technically nonprofits (even health insurance companies), but their operations are typically designed to prioritize revenue generation. Organizing in the US has a more established history of holding for-profit corporations (for which we feel ownership as shareholders or consumers) and government bodies (for which we feel ownership as constituents) to account. As a result, there are limited case studies and playbooks to point to for groups that are hoping to step into health justice work.

Finally, our narratives of healthcare in this country are still quite limited. While cultures around the world have held expansive views of healing for centuries, the predominant view of healthcare today in the United States—in media, in academia, in homes—is that it is 1) a commodity and 2) about the treatment of disease. While many healthcare institutions are increasingly acknowledging and moving towards the SDH model described above, the predominant view is still that of the clinic and medical prescription.

To imagine beyond that narrow view, many movements and communities have decided to design their own alternative systems of healing and care (which we will cover in the third article of this series). As such work happens, our existing system continues to generate impassioned stories and a desire to take action, assets that a few determined organizations are working to translate into individual and collective power. The need to ensure that the holders of painful experiences of healthcare have a say in what health looks like at the individual, community, and societal levels has never been more urgent.

0 Commentaires