This article is from a series, published by NPQ in partnership with the First Nations Development Institute (First Nations), that lifts up Native American voices to highlight issues concerning environmental justice in Indian Country. It was first published online, on March 31, 2020, and is republished here with minor alterations.

Fishponds, loko i‘a, were things that beautified the land, and a land with many fishponds was called “fat” land (‘āina momona).

—Samuel Kamakau,

Na Hana a ka Po‘e Kahiko: Works of the People of Old

There are many lessons to be learned from Indigenous aquaculture practices, especially in the areas of climate mitigation, adaptation, resilience, resource management, and food sovereignty. Today, Native Hawaiians are working to reclaim physical spaces, improve resilience, and resurface Indigenous ways of knowing, observing, managing, and thriving in the Hawaiian island environment, drawing on practices that have been developed over many centuries.

One of the most isolated archipelagos on the planet, Hawai‘i is about 2,500 miles away from any other place in the world. As the landscape’s spirit and history of our community are revived, so are the insightful and innovative practices of our Native Hawaiian ancestors. This knowledge, the lessons learned, and the people who practice them are stories of inspiration for our greater community and the global movement of Indigenous people and local communities of which they are a part.

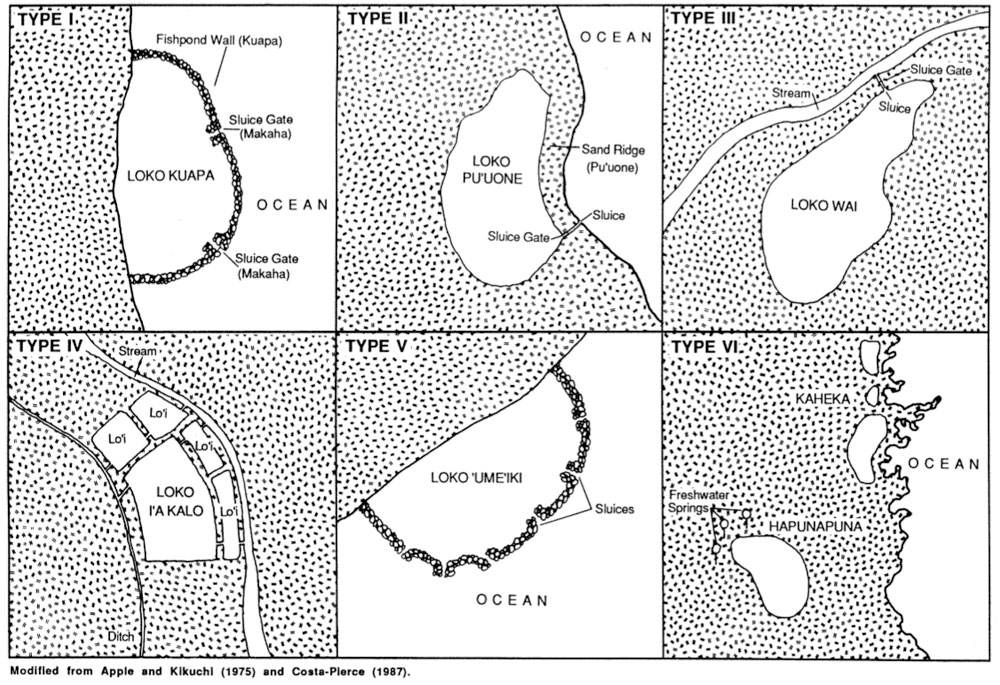

Hawai‘i is home to some of the first known aquaculture practices in the Pacific. Loko i‘a (fishponds) are an advanced, extensive form of aquaculture found nowhere else in the world.1 While techniques of herding or trapping adult fish in shallow tidal areas, in estuaries, and along their inland migration can be found around the globe, Hawaiians developed loko i‘a that are technologically unique, advancing the cultivation practice of mahi i‘a (fish farmers). They exist as part of the traditional Native Hawaiian infrastructure for biocultural (integrated natural and cultural) resource abundance, or ‘āina momona (which literally translates as “fat lands”). ‘Āina momona stretch across and uplift the ecological and cultural functioning of the entire watershed, from mountaintop to nearshore. As Native Hawaiian historian Samuel M. Kamakau described, the existence of a loko i‘a within a functioning ecosystem or landscape alone indicates abundance.

Hawai‘i’s traditional biocultural system for natural resource management once supported close to a million people—almost as many people as inhabit our state today—who relied entirely on island resources for survival.2 In this, loko i‘a served a sophisticated and essential role in protein production, producing an estimated 300 pounds of fish per acre per year.3 Statewide surveys identified 488 loko i‘a on six of the main Hawaiian islands.4 (See Figure 1.)

Hawaiian innovation is reflected in the variety of loko i‘a design and construction methods, demonstrating an unparalleled understanding of engineering, hydrology, ecology, biology, and agriculture managed holistically within watershed-scale land divisions called ahupua‘a.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, globalization and advancements in refrigeration and transportation transformed food production and thus environmental stewardship practices globally. In Hawai‘i, these forces, population loss from introduced diseases, and rapid sociopolitical change, including the overthrow of the Hawaiian government by American plantation owners in 1893, drove dramatic changes to every aspect of Hawaiian life, including loko i‘a.

Hawai‘i’s famed/infamous history of ranching, pineapple and sugar plantation agriculture, American military land use, and rapid urban development have decimated the infrastructure of a biocultural system that once functioned sustainably across watersheds, from our mountaintops and down to the sea. The loss of Native land tenure has resulted in alienation from traditional stewardship practices like loko i‘a, limits to land access, distancing of communities from decision-making and civic engagement around natural resources, and rapid loss of knowledge and traditional practices of caring for these resources. Today, we suffer the predictable consequences of these circumstances.

The abundance of natural resources has declined severely in the last two hundred years. By some estimates, production from our fisheries and agriculture in native crops like taro has fallen by as much as 90 percent.

Ironically, an estimated 85 to 90 percent of the food eaten in Hawai‘i comes in on a ship or barge.5 Our loko i‘a too are highly degraded. Some are completely covered and unrecognizable, while very few are used for food today. Yet reliance on natural resources endures in rural Hawaiian communities as a tradition that feeds families, creates a strong sense of a unified community, and binds together the social elements necessary for cultural perpetuation.6

Environmental justice speaks to the protection of people from environmental harms—and access to environmental goods—regardless of race, income, or color, and the equitable access to decision-making around environmental health and well-being. The ability of Indigenous communities around the globe to determine our destiny, our relationship to the water, land, and living things that sustain us—thus beats the ethic and very heart of environmental justice.

The 1970s and ’80s saw a broad resurgence of a multiethnic and Native Hawaiian–led movement—known as the Hawaiian Renaissance7—to reassert systems of Native Hawaiian language, health practices, and food production, including loko i‘a practice. This movement continues to grow.

Today, rural and Native Hawaiian communities are building a movement to restore loko i‘a and their surrounding near-shore environments (fisheries, coral, and seaweed beds), and remain steadfast in the knowledge that loko i‘a maintain the potential to contribute to healthy and robust food and ecological systems. Loko i‘a revitalization continues to move hand-in-hand with the revitalization of Hawaiian language, arts, architecture, and diet. Native Hawaiian values, knowledge, and practices around stewardship, management, care, and utility of our natural resources are becoming ever more important to how conservation and business is done in Hawai‘i.

Restoration of loko i‘a commonly targets other related issues of concern in our communities, ranging from community-based economic development to healing substance abuse. These efforts all stem from a common cultural ethic—epitomized in the Hawaiian word lōkahi (unity, harmony)—that holds that the health of people, culture, and place are all deeply entwined. We have seen that the revitalizing work of loko i‘a restores our human communities, as well as our broader interwoven community of native and endangered plants, invertebrates, fishes, and birds.

It was so beautiful for me to create and clean something and make it beautiful. My whole life, I’ve just destroyed things. It was just such a privilege to make something beautiful. Thank you for waking me up and helping me connect to my Hawaiian culture. I thought it was too late already. I thought my kūpuna (elders) had died and left me. I know now, my kūpuna are here. They are in me. I felt them today.

—Reflection from a patient at a substance-abuse treatment center on working around loko i‘a on Mokauea Island, Ke‘ehi

The stewardship efforts of our communities to restore loko i‘a and other local food production and manage our natural resources—healing our relationship to our places, ourselves, and each other—continue to face contemporary challenges that are complex and systemic. Generations of severed familial and community ties to land have decimated the availability and perpetuation of precious traditional ecological knowledge for environmental stewardship and food production in our communities. What remains is highly vulnerable to loss, especially as our elder knowledge-holders age. The funding mechanisms to support these community groups are also vulnerable to reliance on well-intentioned intermediaries and funders who often have a limited time period or alignment to support the community’s work. Existing local, state, and federal policies, institutions, and programs—generally designed from a Western, hierarchical paradigm of resource management—are often ill-suited to address the needs and demands of community-based stewardship practice and revival.

One person standing alone has only one voice . . . it’s not as strong as 100 people standing together.

—Damien Kenison of Ho‘okena, speaking to the power of networks

The formation of networks of Native fishers, farmers, families, and allies is a natural and powerful response to systemic and complex contemporary barriers. The formation of community-organized networks accelerated during the Hawaiian Renaissance, and continues through today. Kua‘āina Ulu ‘Auamo (KUA) is a Native Hawaiian–led organization that serves as a facilitator of “networked work.” After ten years of stewarding this work, KUA was incorporated as a nonprofit in 2013, at the request of fishers, farmers, and community leaders from over thirty rural Hawaiian communities. In strategic planning meetings, these leaders affirmed each community’s mandate to advance place-based natural resource stewardship, and that systemic barriers facing our communities can best be tackled collectively.

The word konohiki means to invite ability [and] willingness. This refers to the ability of a konohiki to organize people for collective endeavors no one family could achieve alone, such as maintenance of irrigation systems to sustain taro patches or surround net harvests.

—Carlos Andrade, Hā‘ena: Through the Eyes of the Ancestors, 2008

More broadly, KUA honors the practice of konohiki in communities across our islands. Throughout Hawai‘i today, grassroots groups and families continue to care for their places with Native Hawaiian values, culture, and intelligence. Through place-based restoration and stewardship rooted in Indigenous science, practice, and a worldview inherently tied to ‘āina (land, earth—literally, “that which feeds”), these efforts to care for our island home have meaningful and immediate ecological and social impact on the people and storied places of Hawai‘i.

In the face of many challenges, and in community self-determination and affirmation of our generational ties to land, Indigenous identity, and each other are the gravitational pull that turns the tide.

KUA’s primary work is to coordinate the people and physical resources needed to create resonance for conversations within and among the networks we facilitate. The Hui Mālama Loko i‘a is one such network, made up of over sixty sites and a growing community of over one hundred kia‘i loko (fishpond guardians and caretakers).

In February 2020, 170 kia‘i loko and other Indigenous aquaculture leaders from around the Pacific convened in a historic gathering in He‘eia, O‘ahu for a four-day Indigenous aquaculture summit and cultural exchange. The gathering was hosted and led by community organizations Paepae o He‘eia and Kāko‘o ‘O–iwi, with logistical, facilitation, and funding support from KUA and Hawai‘i Sea Grant. Participants engaged in discussions, skills exchange, and field trips to various other loko i‘a across O‘ahu, and included a collective work project to restore 120 feet of kuapaā(wall infrastructure) at He‘eia fishpond.

This gathering provided opportunities for Hawaiian practitioners to talk together about loko i‘a practices and wahi pana (storied places), and builds on a partnership between Hawai‘i and Washington Sea Grant programs to support an Indigenous aquaculture exchange in the Pacific Northwest, which began in 2022 and is ongoing.

The Indigenous aquaculture summit was held ahead of the Aquaculture America 2020 meeting in Honolulu, one of the largest aquaculture trade shows in the world.8 The conference theme: Hawai‘i Aquaculture: A Tradition of Navigating with Innovation, Technology and Culture, was highlighted by plenary speaker Keli‘i Kotubetey, the assistant executive director at Paepae o He‘eia. “We build upon generations of knowledge that help inform our practice in today’s changing environment and economy,” said Kotubetey during the Indigenous summit at He‘eia. “Our kūpuna were experts in areas of climate mitigation, adaptation, resilience, resource management, and food sovereignty. We are excited to share this with the broader community.”

Loko i‘a practice reflects a deep Indigenous understanding of the environmental, ecological, and social processes specific to our islands. In addition to today’s work of reclaiming physical spaces, our collective work is to also reclaim the innovation and resilience inherent to our Indigenous ways of knowing, observing, managing, and thriving in our environment. The work of the Hui Mālama Loko i‘a gives voice to some of Hawai‘i’s most skilled and committed natural resource managers in using, sharing, and practicing traditional approaches to resource management to meet modern challenges and restore some of Hawai‘i’s most cherished places.

As we look to the future, we envision a revival of the famed abundance of loko i‘a, while also contributing to a broader movement to reclaim Native intelligence and innovation in our land and food systems. Today, loko i‘a serve as important kīpuka—which literally means oasis/oases, but figuratively means receptacle(s)—for the renewal of traditional practices and values in contemporary ways; but the work of loko i‘a caretakers (and many other Hawaiian subsistence practitioners) is systemically underresourced, undervalued, and overlooked.

The restoration of loko i‘a provides inspiration for Native Hawaiians and the larger community to renew ‘āina momona, an abundant, productive ecological system that supports community well-being. The bigger need— and opportunity—is great: to grow and strengthen the social and cultural infrastructure supporting traditional ecological knowledge and the capacity of Indigenous practitioners to share, teach, and perpetuate their work.

The name of our organization, Kua‘āina Ulu ‘Auamo, means “grassroots growing through shared responsibility”; the acronym, KUA, means “back.” We believe that empowered community stewardship efforts lead to our vision of an abundant, productive ecological system that supports community well-being: ‘ĀINA MOMONA.

Notes

- Patrick Vinton Kirch, Feathered Gods and Fishhooks: An Introduction to Hawaiian Archaeology and Prehistory (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1985).

- Gilbert Johnston, review of Before the Horror: The Population of Hawai‘i on the Eve of Western Contact, by David E. Stannard, American Anthropological Association 15, no. 2 (November 1992): 12–14; and see David E. Stannard, Before the Horror: The Population of Hawai‘i on the Eve of Western Contact (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1989).

- Barry Costa-Pierce, “Aquaculture in Ancient Hawaii,” BioScience 37, no. 5 (May 1987): 320–31.

- DHM Planners et , Hawaiian fishpond study: islands of O‘ahu, Moloka‘i, and Hawai‘i (Honolulu, HI: DHM Planners, 1989).

- Office of Planning, Department of Business Economic Development & Tourism, Increased Food Security and Food Self-Sufficiency Strategy (in cooperation with the Department of Agriculture, State of Hawaii, October 2012).

- Davianna McGregor, NaāKua ‘A–ina: Living Hawaiian Culture (Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2007).

- Sam ‘Ohu Gon and Kawika Winter, “A Hawaiian Renaissance That Could Save the World,” American Scientist 107, no. 4 (July–August 2019): 232.

- Aquaculture America 2020: Hawai‘i Aquaculture: A Tradition of Navigating with Innovation, Technology and Culture, National Conference & Exposition of National Aquaculture Association, February 9–12, 2020, Honolulu, HI.

0 Commentaires